Introduction

“At the technical level, the answer to how is gelatin made lies in the controlled partial hydrolysis of collagen: a sophisticated process where connective tissues—such as bovine hides or porcine skin—undergo specific acid or alkaline pre-treatment to destabilize their fibrous structures. This critical step is followed by a sequence of multi-stage warm water extractions, ion-exchange purification, and vacuum drying, effectively converting naturally insoluble collagen into the soluble, high-purity protein powder that forms the backbone of modern softgels and functional gummies.”

The Raw Material Sourcing

Before a single drop of water is heated, the quality of gelatin is already determined by its source. Gelatin is not synthesized; it is extracted. Therefore, the integrity of the supply chain is paramount. The industry relies on three primary pillars of collagenous raw materials, each offering distinct characteristics for the final application:

- Porcine Skin (Pork): Historically the most common source for food applications. It typically undergoes acid processing (Type A) to produce gelatin with excellent clarity and high bloom strength.

- Bovine Hides & Bones (Beef): The preferred choice for pharmaceutical hard capsules. Bovine bones are processed into “ossein” (demineralized bone) before extraction. This source generally undergoes alkaline processing (Type B).

- Marine Sources (Fish Skin & Scales): A rapidly growing segment driven by “clean label” trends and specific dietary preferences (pescatarian), known for a lower melting point and unique viscosity profiles.

Expert Insight: Traceability & Safety

For a supplement ingredient expert, sourcing is synonymous with safety. The gelatin industry operates under strict regulations that rival the pharmaceutical sector.

- Fit for Human Consumption: It is a non-negotiable standard that all raw materials must be derived from animals that have been veterinary-inspected and cleared for human consumption.

- The BSE Control: specifically for bovine sources, the control of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) is critical. Premium gelatin manufacturers strictly source from countries classified as having a “negligible BSE risk” by the OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health), ensuring the absolute safety of the supply chain from the farm to the capsule.

The Certification Gatekeepers: Kosher & Halal

Sourcing decisions are rarely just about chemistry; they are often about market access. The cultural and religious certifications—Kosher and Halal—are decisive factors in raw material selection.

- While porcine gelatin is functionally excellent, it is excluded from these massive global markets.

- To meet these standards, manufacturers must use bovine or marine sources processed under strict religious supervision. This dictates not just what raw material is bought, but how it is collected and segregated right from the slaughterhouse.

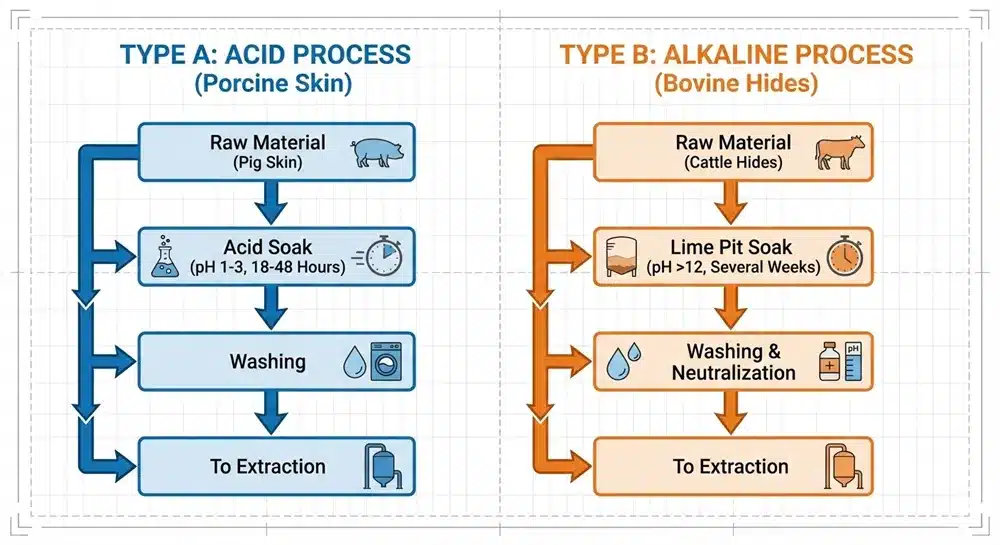

Pre-treatment: The Crucial Split

Once the raw material arrives, the manufacturing process reaches a critical fork in the road. Collagen is naturally tough—its triple-helix structure is held together by strong cross-links designed to support animal tissue. Before we can extract gelatin with warm water, we must first “unlock” these bonds.

This stage, known as pre-treatment or conditioning, determines the genetic makeup of the final gelatin, classifying it into two distinct families: Type A or Type B.

Type A Gelatin: The Acid Process

- The Target: Primarily used for Porcine Skin (Pig Skin).

- The Process: Pig skin contains collagen that is less cross-linked and structurally “younger” than bovine hide. Therefore, it requires a milder, faster treatment. The skins are soaked in a dilute acid solution (typically sulfuric or hydrochloric acid).

- The “Fast Track”: This process is aggressive but efficient. It effectively opens up the collagen structure in a matter of hours or days (typically 18 to 48 hours).

- Chemical Profile: Because the acid treatment is brief, it causes minimal chemical modification to the protein side chains. As a result, Type A gelatin retains a high Isoelectric Point (pI) of pH 7.0 – 9.0, similar to the native collagen. It produces almost no ammonia during processing.

Type B Gelatin: The Alkaline/Lime Process

- The Target: Primarily used for Bovine Hides & Bones (Ossein).

- The Process: Bovine collagen is highly cross-linked and complex. Acid isn’t enough to penetrate this tough structure. Instead, the material is submerged in a lime slurry (calcium hydroxide) or alkali solution.

- The “Deep Clean”: This is a slow, transformative process known as “liming.” It requires patience, lasting anywhere from several weeks to a few months. This prolonged exposure not only breaks down the collagen bonds but also thoroughly removes non-collagen proteins, fats, and other impurities.

- Chemical Profile: The long alkali treatment converts glutamine and asparagine amino acids into glutamic and aspartic acids. This chemical shift (deamidation) drastically alters the electrical charge of the molecule, resulting in a much lower Isoelectric Point (pI) of pH 4.7 – 5.2.

Why This Distinction Matters?

For a supplement formulator, knowing whether you are using Type A or Type B is not just trivia—it’s chemistry.

- Type A is often preferred for its clarity and speed in acidic environments.

- Type B is the standard for pharmaceutical hard capsules due to its robust stability.

- Warning: Mixing Type A and Type B gelatin in a liquid solution without adjusting the pH can cause them to interact and precipitate (clump together) because they carry opposite electrical charges at neutral pH.

Extraction: The Multi-Stage Approach

With the collagen structure now “opened” by pre-treatment, the material is ready for extraction. However, contrary to the kitchen logic of making bone broth, industrial gelatin extraction is not a simple “one-pot” boiling process. It is a precise, fractional extraction method designed to harvest gelatin in specific quality tiers.

We employ a multi-stage extraction process using strictly controlled warm water. This prevents thermal degradation and ensures we capture the collagen at its peak performance.

The Temperature Ladder

The extraction happens in a series of steps, typically 3 to 6 stages, with the temperature rising incrementally for each new batch of water.

- The First Extract (The Premium Cut):

- Temperature: Controlled at a gentle 50-60°C.

- Result: This stage yields the highest quality gelatin. Because the thermal stress is minimal, the protein chains remain long and intact. The result is a product with the highest Bloom strength (often 250+ Bloom), the lightest color, and the highest clarity. This is the “Extra Virgin Olive Oil” equivalent of the gelatin world.

- Subsequent Extracts (The Gradient):

- Temperature: For each subsequent extraction, the water temperature is raised (e.g., to 70°C, then 80°C).

- Result: As heat increases, the hydrolysis becomes more aggressive. The protein chains are chopped into shorter lengths. Consequently, the Bloom strength decreases and the color deepens with each stage.

- The Final Extract:

- Temperature: Reaches near boiling point (~100°C).

- Result: This yields the lowest Bloom gelatin (low viscosity), which is often used for specific confectionary applications or technical uses where gelling power is less critical.

Expert Insight: The Art of Blending for Softgels

You might ask: “If the first extract is the best, why don’t we use it for everything?”

The answer lies in functionality. In the world of softgels (Soft Gelatin Capsules), “best” is defined by balance, not just strength.

- Mechanical Strength vs. Dissolution: A softgel shell needs high Bloom gelatin to be robust enough to hold the oil and withstand shipping (mechanical strength). However, if the Bloom is too high, the shell might become too tough or brittle, delaying the release of the medicine in the stomach.

- The Solution: Manufacturers rarely use a single extract. Instead, we blend high-Bloom (First Extract) and medium-Bloom fractions. This engineered blend creates a shell that is tough enough to survive the supply chain but soluble enough to dissolve rapidly upon ingestion.

Purification & Refinement: From Crude Extract to Pharma Grade

The liquid drawn from the extraction tanks is gelatin, but it is far from the finished product. At this stage, it is a dilute solution (approx. 3-4% concentration) containing suspended fats, proteins, and inorganic salts. To transform this “soup” into a pharmaceutical-grade excipient, it must cross the most rigorous processing threshold in the entire plant.

This stage is the watershed moment that distinguishes high-quality pharma/food gelatin from lower industrial grades.

1. Filtration & Clarification

First, the liquid passes through high-efficiency separators and diatomaceous earth filters.

- The Goal: To physically remove suspended solids and residual fats/oils.

- The Result: The cloudy liquid becomes transparent. For high-end applications, clarity is not just aesthetic; it’s a purity indicator.

2. Ion Exchange: The Game Changer

This is arguably the most critical step for chemical purity. The filtered liquid flows through resin columns in a process called Deionization.

- Removing “Ash”: This process strips away inorganic salts (calcium, sodium, magnesium) and heavy metals, technically referred to as reducing the “Ash Content.”

- Why It Matters: For softgel manufacturers, this is non-negotiable. High salt content (high conductivity) can interact with the plasticizers in the softgel shell or the active ingredients inside, leading to cross-linking (shell hardening) or stability issues.

3. Vacuum Concentration

The purified liquid is still mostly water. To remove it without cooking the gelatin to death, we use Vacuum Evaporators.

- Physics at Work: By creating a vacuum, we lower the boiling point of water. This allows us to evaporate moisture at relatively low temperatures, thickening the liquid from a 4% solution into a honey-like syrup (approx. 30% concentration) without thermally degrading the protein chains.

4. UHT Sterilization

Before drying, safety is locked in. The concentrated syrup undergoes Ultra-High Temperature (UHT) sterilization.

- The Shock Treatment: The gelatin is heated to roughly 140°C for just 4-5 seconds.

- The Benefit: This thermal shock instantly kills bacteria and spores but is too brief to damage the gelatin’s bloom strength. It ensures the final powder meets strict microbial limits (e.g., USP/EP standards).

Forming & Drying: The Final Transformation

We now have a purified, sterile, and concentrated gelatin syrup. But customers don’t buy syrup; they buy stable powder or granules. The final leg of the journey focuses on moisture management and particle engineering.

1. Chilling & Extrusion: The “Noodles”

The hot concentrated syrup enters a scraped-surface heat exchanger (often called a Votator). Here, it is rapidly cooled to set into a solid gel state.

- The Shape: The gel is extruded through a die plate, forming long, continuous strips that look remarkably like spaghetti noodles.

- Why Noodles? This isn’t for aesthetics. Creating “noodles” maximizes the surface area, allowing for efficient and uniform airflow during the drying process.

2. Band Drying: The Tunnel

These gel noodles are laid onto stainless steel wire mesh belts that travel through a massive drying tunnel.

- Zoned Drying: The tunnel is divided into zones with precise temperature and humidity controls. The air passes through the mesh and the gelatin bed.

- The Goal: To gently reduce the moisture content from approx. 70% down to a stable 10-12%. If dried too fast, the surface hardens while the inside stays wet (case hardening); if dried too slow, microbial risks increase. It’s a delicate balance.

3. Grinding & Blending: The Art of Consistency

Once dried, the noodles are brittle and hard (known as “flake” or “kibble”). They are then ground into specific granulations (Mesh Sizes) based on customer needs—fine powder for instant drinks, or coarser granules for tableting.

- The Critical Step: Blending

- Expert Insight: Nature is variable. No two batches of skin or bone are identical, meaning no two extraction batches have exactly the same Bloom or Viscosity.

- The Solution: We don’t sell “Batch A” or “Batch B.” We create a “Master Batch.” By blending tons of gelatin from different extractions in massive silos, we homogenize the product. This ensures that the gelatin you buy today performs exactly the same as the gelatin you bought six months ago.

Understanding the Specs: Decoding the COA

For a procurement manager or R&D scientist, the Certificate of Analysis (COA) is the passport of the product. But to truly judge quality, one must look beyond the numbers and understand the physical reality they represent. Here is how to read the three most critical sections of a gelatin spec sheet.

1. Bloom Strength: The Gold Standard of Rigidity

Bloom is not just an arbitrary number; it is a standardized measurement of gel rigidity.

- The Test Method: The definition of Bloom is highly specific. A 6.67% gelatin solution is prepared and chilled at 10°C for 17 hours. A standardized plunger (12.7mm diameter) is then pressed into the gel surface.

- The Definition: The “Bloom Value” is the weight in grams required to depress that plunger exactly 4mm into the gel.

- High Bloom (200-300g): Stiffer, faster setting. Ideal for hard capsules and ballistic gelatin.

- Low/Medium Bloom (100-200g): Softer, more elastic. Ideal for gummies and confectionary.

2. Viscosity: The Flow Factor

While Bloom measures the solid state, viscosity measures the liquid state behavior at 60°C (usually measured in mPa·s or millipoise).

- Why It Matters: This is a production efficiency metric.

- Too High: The gelatin becomes “stringy” or difficult to pump, leading to “tailing” issues in softgel encapsulation or uneven coating.

- Too Low: The shell might be too thin or prone to leaking before it sets.

- Expert Note: Viscosity and Bloom usually correlate (high Bloom ≈ high Viscosity), but different processing techniques (acid vs. alkali) can decouple them to suit specific machinery needs.

3. Microbiological Standards: The Safety Net

Because gelatin is an animal-derived protein, microbiological control is the highest priority. It is not enough to be “clean”; it must be “compliant.”

- Pharmacopoeial Compliance: Premium gelatin must meet the harmonized standards of the USP (United States), EP (European), and JP (Japanese) Pharmacopoeias.

- The Red Lines:

- Total Aerobic Microbial Count (TAMC): Strictly limited (e.g., < 1000 CFU/g).

- Pathogens: There is zero tolerance. Salmonella and E. coli must be strictly “Negative” (Not Detected) in specific sample sizes (usually 10g or 25g).

Conclusion

When we ask “how is gelatin made,” the answer reveals a journey that is equal parts ancient tradition and modern biotechnology. From the careful selection of porcine or bovine sources to the precise molecular scissors of acid or alkaline hydrolysis, every step is engineered to produce a safe, functional, and consistent excipient.

The “Plant-Based” Challenge & Gelatin’s Resilience

We live in an era where “plant-based” is a buzzing trend. While alternatives like HPMC (Hypromellose), starch, and carrageenan have carved out their niche, gelatin remains the undisputed king of the pharmaceutical and nutraceutical world. Why?

- The “Melt-in-Mouth” Factor: Gelatin melts at body temperature (~37°C). This unique thermal reversibility creates a sensory experience and drug release profile that plant gums struggle to mimic perfectly.

- The Oxygen Barrier: For sensitive ingredients like Omega-3s or probiotics, gelatin offers superior protection against oxidation, extending shelf life naturally.

- The Economics: It remains the most cost-effective high-performance film former available.

Final Thought

Gelatin is not just a byproduct; it is a highly sophisticated natural biopolymer. As the industry evolves towards cleaner labels and higher transparency, the manufacturers who master the delicate balance of sourcing, science, and safety—as detailed in this guide—will continue to define the standard for quality health products.